The Technology Quarterly issue from The Economist for August 27, 2016 described the open frontier of space. Check out Remaking the sky. I think that’s behind their paywall, so you may need a subscription.

Here are a few cool things I learned.

A sudden light – Nice description of the SpaceX launch when they recovered a booster back at the original launch site. Puts into context what an amazing step it is to recover a booster.

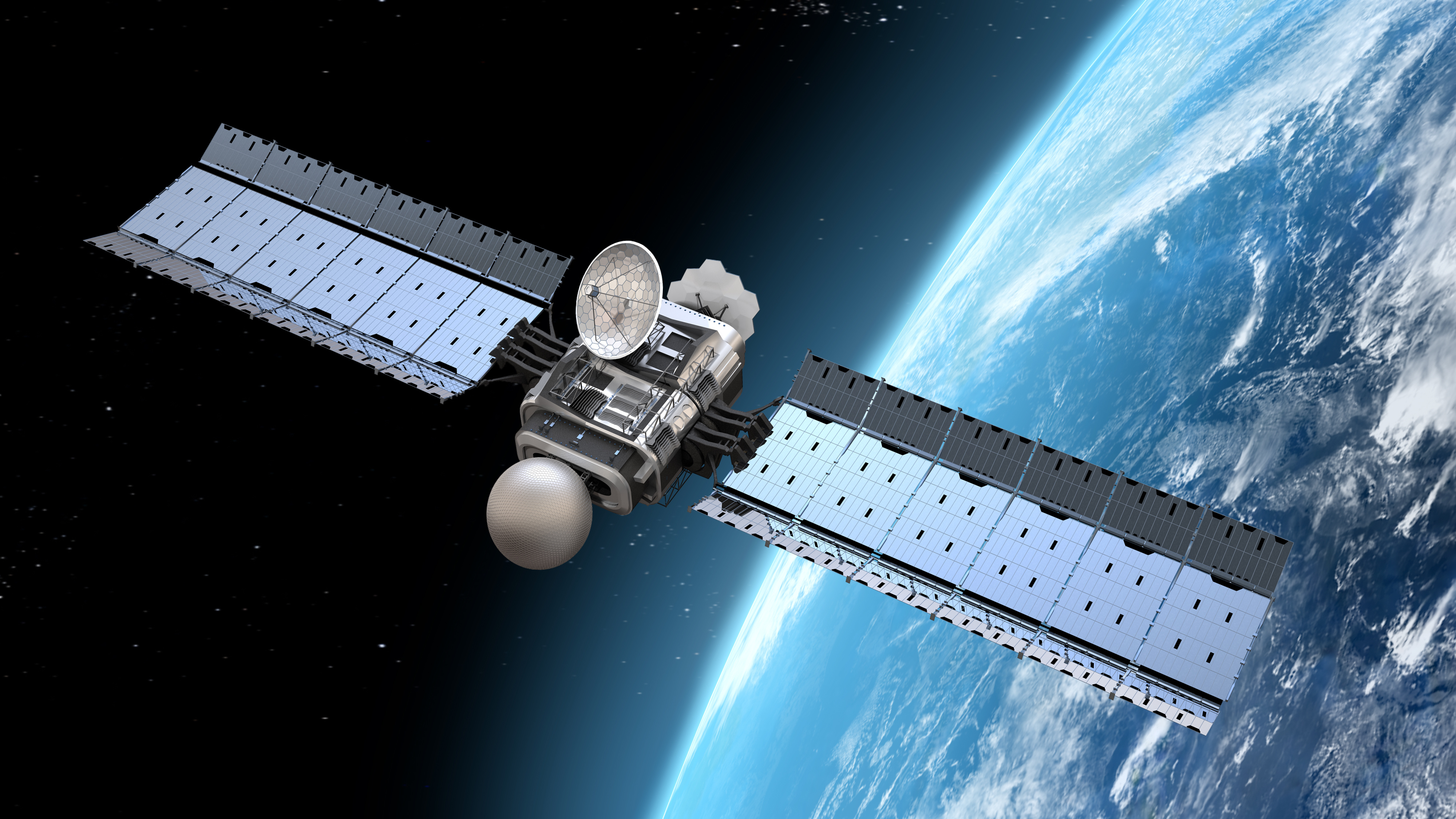

The small and the many – There are four major players in the world of communication satellites: Eutelsat, Inmarsat, Intelsat, and SES.

The typical cost for SES satellites range from $100M up to $300M. The launch cost is in ballpark of $100M. At those prices the entire satellite industry is very risk-averse. I get it. You cannot take a big chance when somewhere between $200M and $400M is on the line.

Tiny satellites, called cubesats, are built in multiples of blocks measured in “1U”, meaning a box 10 cm by 10 cm by 11.5 cm.

Cubesats are revolutionizing the satellite world by dramatically reducing cost and risk. The cost to develop a cubesat is small. One launch can lift a lot of cubesats which drops the cost. They don’t have the power to last very long and don’t have any propulsion, with both factors making it cheaper to experiment and not as risky to something trying something new.

A cool graphic provides background. Spending in the space industry for 2015 is:

- $127B – satellite services

- $106B – ground equipment

- $80B – government programs

- $17B – satellite manufacturing

- $5B – launch industry

Astounding to consider that the parts I find so fascinating, the launch and satellite parts, are a small fraction of the total industry.

Number of satellites in orbit as of December 2015:

- 511 – commercial communication

- 193 – military and civil communications

- 193 – Earth observation

- 166 – research and development

- 110 – Military surveillance

- 97 – navigation

- 69 – scientific

- 41 – meteorological

- 1,381 – total

The biggest value of a satellite for communications or many other applications is to have it orbit over the same spot on earth. This is called a geosynchronous orbit. That would be 36,000 km out, or 21,600 miles.

The payoff of small satellites at a lower elevation is the amount of data that can be handled for a given set of equipment drops “according to the square of its distance from the surface.” I’m not sure how that works but just look at what happens with the square of the distance for a 250 mile orbit and a 21,600 mile orbit:

- 250 mile orbit squared is 62,500

- 21,600 mile orbit is 466 million

That’s a difference of a factor of 7,500. Like I said, I don’t know how that works but you could have a satellite with a fraction of the capability if you could put it at 250 miles instead of 21,600.

The flipside is you would need a huge number of satellites in low earth orbit to provide the coverage as provided by one satellite in geosynchronous orbit.

Here’s another brain-stretcher learning point for me: a sun-synchronous orbit puts a satellite on a pole to pole orbit every 100 minutes. My brain doesn’t get the implications, but I think that means if you put up a constellation of satellites in sun-synchronous orbit, you could get coverage of the whole planet.

The article describes several companies that are planning a large number of satellites to provide coverage of the whole planet. OneWeb plans to put 648 satellites at a 720 mile orbit. They won’t be using cubesats, but aim to build four satellites a day weighing 90 pounds each. SpaceX is pondering a low-orbit system with perhaps 4,000 small satellites.

Launchers: Getting a lift – Yeah, I fall easily for cool graphics. If you have read this far in my meandering post, you really gotta’ check out the illustration of lift vehicles. Included are:

- Kilograms to LEO – boost vehicle – organization – height

- 54,400 kg – Falcon Heavy – SpaceX – 70 m

- 22,800 kg – Falcon 9 – SpaceX – 70m

- 20,000 kg – Ariane 5 – ArianeSpace – 50.5m

- 7800 kg – Soyuz-2.1a – Russia – 46.1m

Then there are three boosters designed to deliver cubesats:

- 200 kg – Alpha – Firefly – 21.6m

- 500 kg – LauncherOne – Virgin Galactic – 16m

- 150 kg – Electron – Rocket Lab – 16m

Oh, all of them are drawn in scale, with a Boeing 747-400 for comparison.

Update: Behind the Black points to an article at SpaceNews, which is reporting Firefly Space Systems furloughs staff after investor backs out. Major investor pulling out of the next round of funding leaves Firefly in cash crunch which in turn led Firefly to layoff its entire workforce.

One thought on “More on the open frontier of space; cool info from The Economist”